R.O.P and Medical Retina

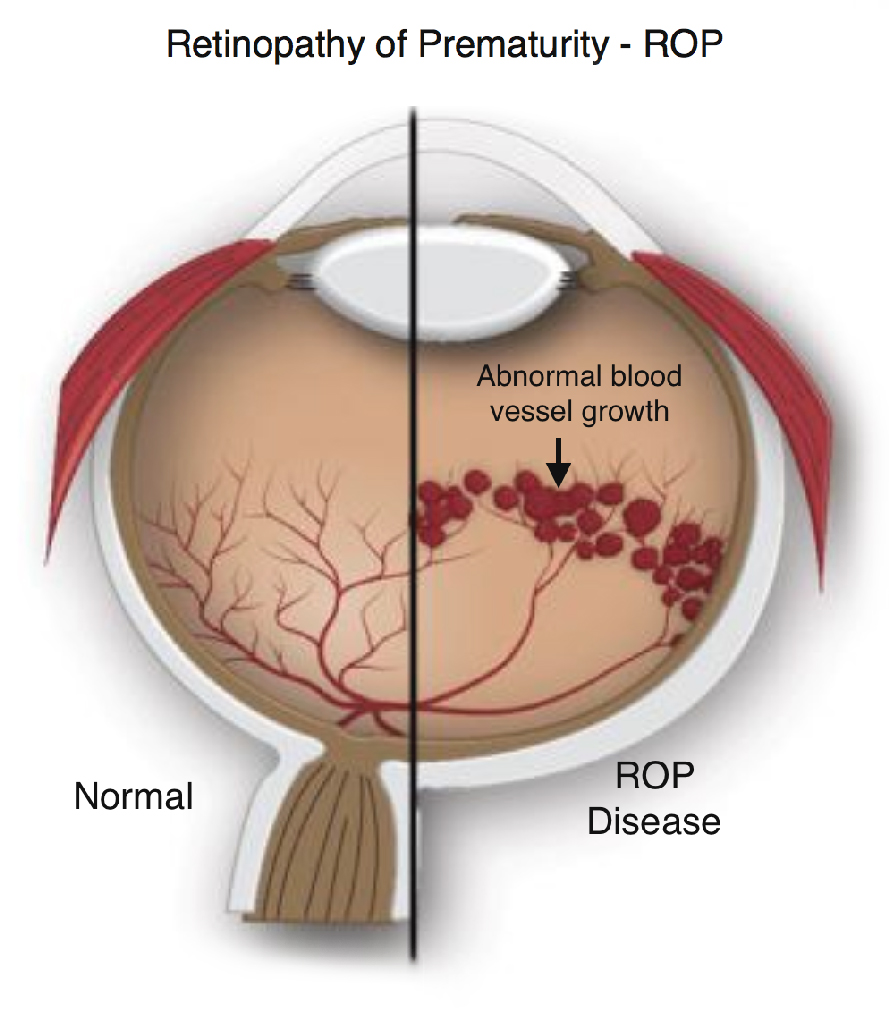

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an eye condition that affects some infants who are born early (premature birth), particularly before 31 weeks. With ROP, abnormal blood vessels form in a baby’s retina. The retina is the layer of tissue at the back of your eye that converts light to electrical signals, which travel to your brain. Your brain processes these signals and creates the images that make up your vision

The abnormal blood vessels that form in ROP usually cause no harm and require no special treatment other than monitoring. Up to 90% of babies with ROP get better without treatment and have normal vision. However, the condition can sometimes get worse and threaten a baby’s vision. In these cases, timely treatment is necessary to prevent permanent retinal damage and vision loss. Without treatment, advanced ROP can lead to blindness.

That’s why healthcare providers recommend screenings for at-risk babies soon after birth. These screenings check for signs of ROP and identify when a baby needs treatment. Your baby’s healthcare provider will tell you if your baby is at risk for ROP. They’ll also tell you when your baby needs screenings. It’s essential to follow the screening schedule they give you to lower your baby’s risk of serious vision problems.

- In the U.S., about 14,000 to 16,000 infants develop ROP each year. About 90% of these babies have a mild form of ROP that doesn’t need treatment. About 1,100 to 1,500 have a severe form that needs treatment. ROP causes legal blindness in 400 to 600 infants per year.

There are usually no obvious signs or symptoms that you can notice in your baby. An ophthalmologist needs to closely examine your baby’s eyes (including blood vessel formation in their retinas) to see if they have ROP.

Disruption to the normal process of blood vessel formation in your baby’s retinas causes ROP.

Your baby needs healthy retinas with normal blood supply to see the world around them. Retinal blood vessels develop throughout pregnancy but aren’t completely formed until close to birth. As a result, babies born prematurely don’t have fully formed blood vessels in their retinas. Those vessels continue to form after birth, but they may develop abnormally.

It’s not always possible to tell which babies will have ROP, but researchers know some factors raise a baby’s risk.

Risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity

Risk factors for ROP include:

- Preterm delivery before 31 weeks. The earlier the delivery, the higher the risk of ROP.

- Birth weight of 1,500 grams (about 3.3 pounds) or less.

- Respiratory distress syndrome.

- Intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding in the brain).

- Infections or other medical problems.

If your baby has one or more risk factors, their healthcare provider will recommend a screening soon after birth to check your baby’s eyes for signs of ROP.

- Untreated, severe cases of retinopathy of prematurity can lead to retinal detachment. This means your baby’s retina pulls away from the supportive tissues around it. Retinal detachment can cause severe vision loss or blindness.

Neonatologists typically identify babies who are at risk for ROP. They refer these babies to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation. During this exam (also called a “screening”), an ophthalmologist uses eye drops to dilate your baby’s eyes and look for signs of ROP. They may take digital pictures of your baby’s retinas. This initial screening usually takes place four to six weeks after birth.

Different countries have different guidelines for which babies should be screened for ROP. In the U.S., infants are typically screened if they:

- Have a gestational age of 30 weeks or less.

- Have a birth weight of 1,500 grams (3.3 pounds) or less.

- Have a higher gestational age or birth weight but have other risk factors for ROP.

Your baby may need additional screenings every one to three weeks, or according to the timeline their provider gives you. Your baby’s ophthalmologist will tell you when they no longer need these exams. This is usually when the blood vessels in your baby’s retinas are fully formed and there’s no risk of retinal detachment.

If the ophthalmologist diagnoses your baby with ROP, they’ll use a staging system to identify the condition’s severity.

Retinopathy of prematurity stages

Ophthalmologists assign a stage to each case of ROP to help describe its severity and the need for treatment. These stages range from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most severe:

- Stages 1 and 2: Mild to moderate ROP that usually goes away without treatment.

- Stage 3: ROP that may need treatment to prevent retinal damage or detachment.

- Stage 4: Severe ROP that leads to partial retinal detachment and requires urgent treatment.

- Stage 5: Severe ROP that leads to total retinal detachment and requires urgent treatment. Vision loss or blindness may still result despite treatment.

Other terms you may hear include:

- Aggressive retinopathy of prematurity: A severe case of ROP that quickly gets worse.

- Plus disease: Severe ROP that includes the presence of widened (dilated) and wavy (tortuous) blood vessels in the retina.

Treatment options for retinopathy of prematurity include:

- Laser therapy. This treatment creates a pattern of small burns on the outer edges of your baby’s retina. These burns prevent abnormal blood vessels from forming. Laser therapy successfully treats ROP about 90% of the time.

- Anti-VEGF therapy. This treatment involves injections (shots) into your baby’s eye to deliver medication that stops abnormal blood vessel growth.

Your baby’s ophthalmologist will tell you the pros and cons of these treatments and explain the most suitable treatment plan for your baby.

If your baby has a retinal detachment (stage 4 or 5 ROP), they’ll need further treatment, typically with a retina specialist. For example, the retinal specialist may recommend a surgery called a vitrectomy.

Your baby needs treatment if they’re at risk for retinal detachment, or if retinal detachment has already occurred. Your baby’s ophthalmologist will determine the best timing for treatment based on the ROP stage and findings from screenings.

ROP happens due to premature birth. Therefore, any steps you can take to lower your risk of early delivery can help lower your baby’s chances of developing ROP. It’s important to seek medical care during pregnancy and follow your provider’s guidance.

It’s also important to remember that sometimes, premature birth can’t be avoided, even if you follow all available advice. If this happens, don’t blame yourself. Advances in treatments and technology help babies born prematurely to be healthy and have a good prognosis.

ROP often goes away on its own without permanent damage to your baby’s retina or vision. However, severe cases of ROP need treatment to prevent complications like retinal detachment and vision loss.

Talk to your baby’s ophthalmologist to learn what treatment they may need and how ROP may affect their vision in the future.

The most important thing you can do is take your baby to all of the screening appointments that their ophthalmologist recommends. These screenings are vital for diagnosing and treating ROP quickly enough to lower the risk for permanent vision loss.

Babies who receive treatment for ROP need lifelong follow-up visits. These are especially important during early childhood. Your baby’s ophthalmologist will look for signs of abnormal blood vessel formation. This can happen despite successful treatment years prior.

Babies born prematurely who don’t have ROP also need regular eye exams. That’s because they face an increased risk of certain eye problems, including:

- Amblyopia (lazy eye).

- Strabismus (crossed eyes).

- Glaucoma.

Ask your baby’s ophthalmologist how often they should have eye exams, and stick to this schedule.

Questions you can ask your baby’s ophthalmologist to learn more about retinopathy of prematurity include:

- Is my baby at risk for retinopathy of prematurity?

- How often does my baby need screenings for ROP?

- When might my baby need treatment?

- What is the best treatment option?

- What are the benefits and risks of treatment?

- What follow-up visits will my baby need after treatment?

- What is my baby’s outlook?