Retinal Deatachment

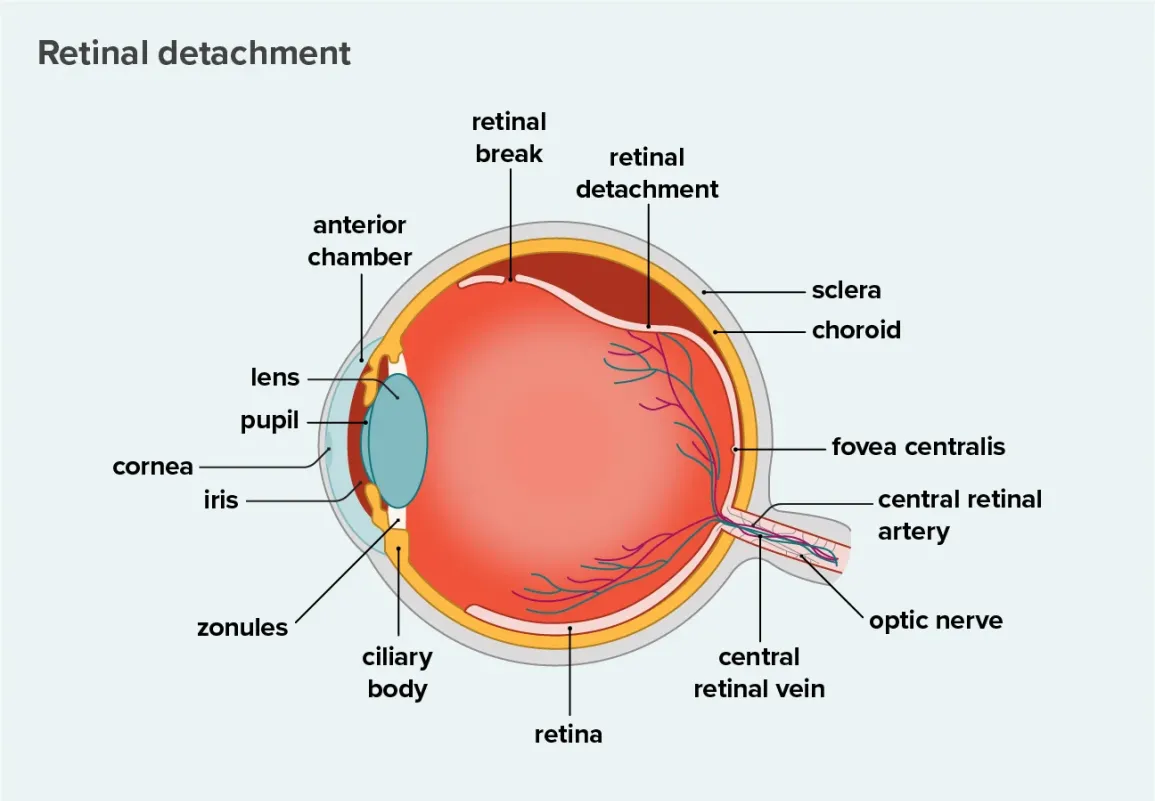

Retinal detachment describes an emergency situation in which a thin layer of tissue (the retina) at the back of the eye pulls away from its normal position.

Retinal detachment separates the retinal cells from the layer of blood vessels that provides oxygen and nourishment to the eye. The longer retinal detachment goes untreated, the greater your risk of permanent vision loss in the affected eye.

Warning signs of retinal detachment may include one or all of the following: reduced vision and the sudden appearance of floaters and flashes of light. Contacting an eye specialist (ophthalmologist) right away can help save your vision.

Retinal detachment is a painless but serious eye condition. It happens when your retina, the layer of tissue at the back of your eye, detaches from the tissues that support it. A detached retina affects your vision and can lead to blindness.

Your retina senses light and sends signals to your brain so you can see. When your retina pulls away from the tissues that support it, it loses its blood supply. The blood vessels in those tissues carry nutrients and oxygen to your retina.

Call your eye care provider or go to the emergency room (ER) right away if you notice:

- More eye floaters than usual.

- Flashes of light

- A shadow in your vision.

These can be symptoms of a detached retina. Don’t wait to see if you feel pain. Your provider will want to start treatment as soon as possible.

Types of retinal detachment

There are three types of retinal detachment:

- Rhegmatogenous: This is the most common type and usually happens as you get older. A small tear in your retina lets the gel-like fluid called vitreous humor travel through the tear and collect behind your retina. The fluid pushes the retina away, detaching it from the back of your eye. As the vitreous shrinks and thins with age, it pulls on the retina, tearing it.

- Tractional: In this type of detached retina, scar tissue on your retina can pull it away from the back of your eye. Diabetes is a common cause of these retinal detachments. Extended periods of high blood sugar can damage blood vessels in your eye and cause scar tissue. The scars and areas of traction (pulling) can get bigger, tugging your retina away from the back of your eye.

- Exudative: This type of retinal detachment happens when fluid builds up behind the retina even though there’s no retinal tear. As the fluid collects, it pushes your retina away from supporting tissue. The main causes of fluid buildup are leaking blood vessels or swelling behind the eye, which can happen from conditions like uveitis (eye inflammation).

Estimates for the incidence of retinal detachment vary. (The incidence is the number of new cases in a set period of time, usually a year.) One figure estimates incidence in the U.S. at 1 in 10,000 people. Another study estimates the annual risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the most common type, at 6.3 to 17.9 per 100,000 people.

Some people don’t notice any symptoms of retinal detachment, while others do. It depends on severity — if a larger part of the retina detaches, you’re more likely to experience symptoms.

Symptoms of a detached retina can happen suddenly and include:

- Seeing flashes of light (photopsia).

- Seeing a lot of floaters — flecks, threads, dark spots and squiggly lines that drift across your vision. (Seeing a few here and there is normal and not cause for alarm.)

- Darkening of your peripheral vision (side vision).

- Darkening or shadow covering part of your vision.

- Risk factors and causes for detached retinas include:

- Aging.

- Eye injury.

- Having a previous retinal detachment or a family history of retinal detachment.

- Having a previous eye surgery.

Having certain eye conditions also raises your risk for retinal detachment, such as:

- Being very nearsighted.

- Posterior vitreous detachment, where the thick fluid in the middle of the eye (vitreous) pulls away from the retina.

- Other conditions that affect your retina or choroid, like lattice degeneration (retina thinning) or diabetes-related retinopathy.

- Certain inherited eye disorders

- A history of retinal tears or detachments in the other eye.

If you’re at high risk for retinal detachment, talk to your healthcare provider. Your provider can help you set an eye exam schedule and suggest other steps to protect your eye health.

Having a detached retina is a serious condition that can cause loss of vision. Permanent blindness can happen as quickly as a few days.

You need an eye exam to diagnose retinal detachment. Your eye care provider will use a dilated eye exam to check your retina. They’ll put eye drops in your eyes. The drops dilate, or widen, the pupil. After a few minutes, your provider can get a close look at the retina.

Your provider may recommend other tests after the dilated eye exam. These tests are noninvasive. They won’t hurt. They help your provider see your retina clearly and in more detail:

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): Most often, you’ll get dilating eye drops for this imaging. Then you sit in front of the OCT machine. You rest your head on a support so it stays still. The machine scans your eye but doesn’t touch it.

- Fundus imaging: Your provider may take wide-angle images of your retina. Your provider usually dilates your eyes for this test.

- Eye (ocular) ultrasound: You won’t need dilating drops for this scan, but your provider may use drops to numb your eyes so you won’t feel any discomfort. You sit in a chair and rest your head on a support, so it stays still. Your provider gently places an instrument against the front of your eye to scan it. Next, you sit with your eyes closed. Your provider puts gel on your eyelids. With your eyes closed, you move your eyeballs as your doctor scans them with the same instrument.

- Computed tomography (CT scan) : This imaging test combines X-rays with a computer and is usually used if there’s a history of trauma or possible penetrating eye injury.

Your eye care provider will discuss treatment options with you. You may need a combination of treatments for the best results.

Treatments include:

- Laser therapy or cryopexy.

- Pneumatic (gas bubble) retinopexy.

- Scleral buckle.

- Vitrectomy.

Laser (thermal) therapy or cryopexy (freezing)

Sometimes, your provider will diagnose a retinal tear before the retina starts pulling away. Your provider uses a medical laser or a freezing tool to seal the tear. These devices create a scar that holds the retina in place.

Pneumatic retinopexy

Your provider may recommend this approach for the right candidates. During pneumatic retinopexy:

- Your provider injects a small gas bubble into the eye.

- The bubble presses against the retina, closing the tear.

- You may need laser or cryopexy (freezing) to seal the tear.

- Your body reabsorbs the fluid that collected under your retina. Your retina can now stick to your eye wall the way that it should. Eventually, your body also absorbs the gas bubble.

After surgery, your provider will recommend that you keep your head still for a few days to promote healing. Your provider may also tell you what position you should lie in or sleep in.

These recommendations may seem uncomfortable or annoying, but they’re particularly important. It’s a short-term sacrifice for long-term benefits.

Scleral buckle

During a scleral buckle surgery:

- Your provider surgically places a silicone band or sponge (buckle) around the eye.

- The band holds the retina in place and stays there permanently. You can’t see the band.

- Your provider seals the tear with a laser or cryopexy.

- Your provider may inject a gas bubble or drain the fluid under the retina to help reattach it.

Vitrectomy

During a vitrectomy, your provider:

- Surgically removes the vitreous.

- Uses laser or freezing to seal all retinal tears or holes.

- Places a bubble of air, gas or oil in the eye to push the retina back in place.

If your provider uses an oil bubble, you’ll have it removed a few months later. Your body reabsorbs gas and air bubbles. If you have a gas bubble, you may have to avoid activities at certain altitudes. The altitude change can increase the size of the gas bubble and the pressure in your eye. You’ll have to avoid flying and traveling to high altitudes. Your provider will tell you when you can start these activities again.

Complications/side effects of treating retinal detachment

While surgery to reattach your retina is often very successful, any surgery can have risks or complications. These risks and complications include:

- Bleeding.

- Infection.

- Higher pressure in your eye (intraocular pressure).

- The chance that you may need another surgery.

- Membranes that form after surgery that can shrink and pull tissues out of place. The name for this is proliferative retinopathy or epiretinal membrane.

- Rapid cataract formation that requires additional cataract surgery.

After treatment for a detached retina, you may have some discomfort. It can last for a few weeks. Your provider will discuss pain medicine and other forms of relief. You’ll also need to take it easy for a few weeks. Talk with your provider about when you can exercise, drive and get back to your regular activities.

Other things you can expect after surgery:

- Eye patch: Wear the eye patch for as long as your provider tells you to do so.

- Head position: If your provider put a bubble in your eye, follow instructions for your head position. Your provider will let you know the position your head should be in and how long to keep it there to help heal your eye.

- Eye drops: Your provider will instruct you on how to use the drops to help your eye heal.

- Improved vision: About four to six weeks after surgery, you’ll start to notice your eyesight improving. It may take a few months until you notice the full effects.

You can’t prevent rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, but you can take steps to lower your risk:

- Get regular eye care: Eye exams protect your eye health. If you have nearsightedness, eye exams are especially important. Myopia makes you more prone to retinal detachment. Your eye care provider should include dilated exams to find small retinal tears.

- Stay safe: Use safety goggles or other protection for your eyes when playing sports or doing other risky activities.

- Get prompt treatment: If you notice detached retina symptoms, see your eye care provider right away or go to the emergency room.

- Maintain your overall health: Manage chronic conditions, eat balanced meals and get regular exercise.

You can help to prevent diabetes-related tractional retinal detachment by improving your blood glucose levels and blood pressure.

People who have an average risk of eye disease should get eye exams once a year. If you’re at higher risk for eye disease, you may need checkups more frequently. Talk to your provider to figure out your best exam schedule.

Your outlook depends on factors like how clear your vision was before the retinal detachment, how extensive your detachment was and if there are any other complicating factors. Your provider will talk to you about what type of vision improvement you can expect.

In general, surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is highly successful — the repair works about nine out of 10 times. Sometimes, people need more than one procedure to return the retina to its place.

It’s possible to get a detached retina more than once. You may need a second surgery if this happens. Talk to your provider about preventive steps you can take to protect your vision.

It’s essential that you follow the instructions you get from your eye care provider about positioning and about your activities.

Ask your provider for suggestions on how to make things easier, like using a firm neck pillow to help keep your head in place. If you must lie face down or stay in that position for most of your time, your provider’s office can help you get face-down equipment for your home.

Your surgeon’s instructions will list situations that are emergencies, but you should contact your provider or get emergency help if you:

- Have severe, unexpected pain.

- Have symptoms of an infection, such as swelling or a fever.

- Have unexpected discharge from your eye.

- Have a sudden decrease in your ability to see.

If you have retinal detachment (or face a higher risk), ask your provider:

- Which retinal detachment treatment is best for me?

- Will I need surgery?

- How can I protect my eye health after surgery?

- How often should I have eye exams?

- What else can I do to lower my risk of retinal detachment?